| Meteorite Name: | L'Aigle |

| Location: | France |

| Classification: | L6 Chondrite |

| Witnessed Fall: | Yes |

| Date and Time: | April 26, 1803 (1300 hrs) |

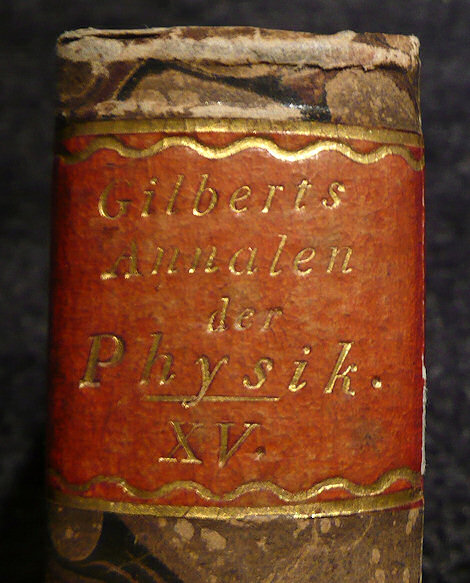

| TKW: | ~ 37 kilograms |

| Remarks: | This is the most historic meteorite fall ever, representing the Copernican or Darwinian moment in meteoritics. Ernst Chladni published his report on meteorites, making the case that these rocks were indeed falling from the sky, a couple of months before the historic Siena witnessed fall of 1794, in Italy. In spite of that fact, the Siena fall was studied by scientists and, due to the coincidence of a Mount Vesuvius eruption on 18 hours earlier, was determined to be material from a volcanic ejection (which, of course, explained why the rock was both burned and had fallen from the sky). A year later, another stone was witnessed to fall in Wold Cottage, England, and the scientific determination was similar. This time it was established that the rock had been struck by lightning (which, of course, explained why witnesses saw a light in the sky and that this rock, as well, had been burned). Then at 1:00 pm on a clear afternoon in L'Aigle, France, 37 kilograms of meteorites were witnessed to fall by numerous prominent citizens - business owners, political leaders and the like - and a 29-year-old scientist, Jean Baptiste-Biot, was commissioned to study the event. His comprehensive report, which included the first strewn field map on record, was the tipping point for immediate worldwide acceptance of the fact that rocks absolutely do fall from space. While Chladni was the catalyst via much of the early work he accomplished - and is still known by many as the father of meteoritics - it was the Biot report that was the catalyst. Though the world is much different today, in this time the French had the final say when it came to things scientific. That fact, in combination with the thoroughness of the report and the large number of reputable witnesses, led to this event being the most important in the history of meteoritics. In addition to the historic nature of this fall, there were also some interesting happenings on the ground upon impact. In the village of St. Michel one stone fell on the pavement of the church yard. The stone ricocheted from the pavement about one foot back into the air and came to rest and the feet of the chaplain who happened to be in the churchyard at the time of the fall. Near the village of Bas Vernett, a pear tree was hit by a stone which sheared a branch off of it. In the village of Mesle, the roof ridge of a house was hit, and a large bar of wood came loose before the stone rolled down the roof and fell to the ground. In the village of Des Anées, a wirepuller named Mr. Piche was hit on the arm by a small stone (and he reportedly dropped the stone instantly after picking it up because it was very hot); in addition to Mbale and Sylacauga, this is, therefore, the third and only other meteorite to have hit a human being. It's sometimes hard to pick a number two, but this specimen is easily my personal favorite in the collection. More information about the L'Aigle Biot report can be found in Matthieu Gounelle's paper, "The meteorite fall at L'Aigle and the Biot report: exploring the cradle of meteoritics". You can also see a scan of the German version of Biot's report, "Detailed News from the rain of stones at L'Aigle on April 2th, 1805". As an added treat, you can hear a French theatrical version of Biot's report at the Canal Académie Website. |

| |

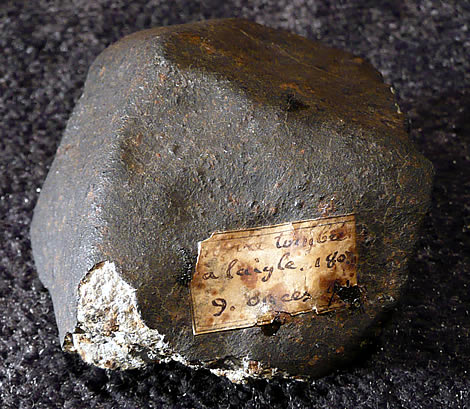

| 277.6 gram oriented, complete specimen (leading edge) | |

| |

| 277.6 gram individual (reverse detail showing contrasting morphology) | |

| |

| 277.6 gram individual (alternate angle reverse detail) | |

| |

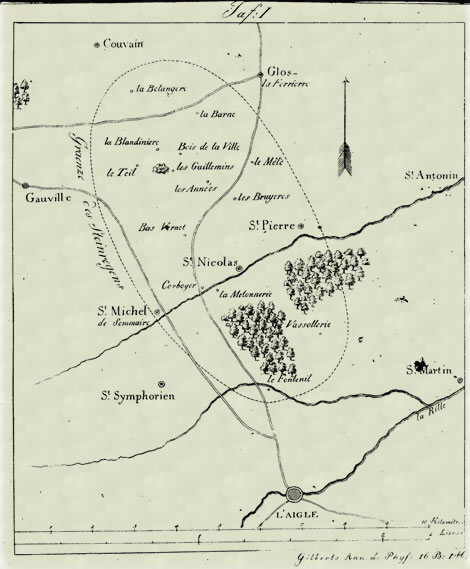

| L'Aigle strewn field map from J. B. Biot's legendary report | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

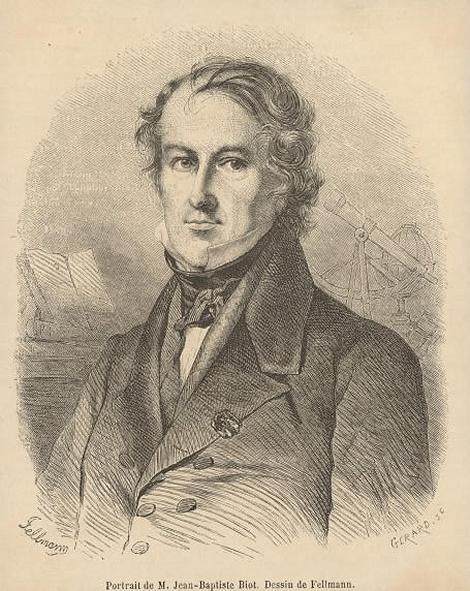

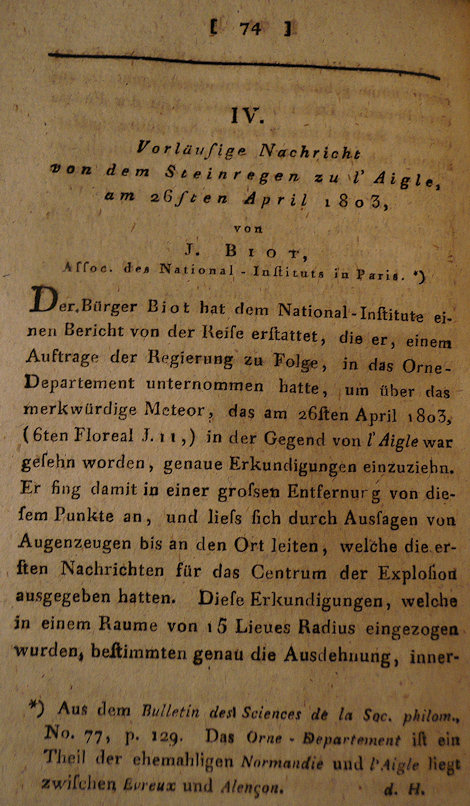

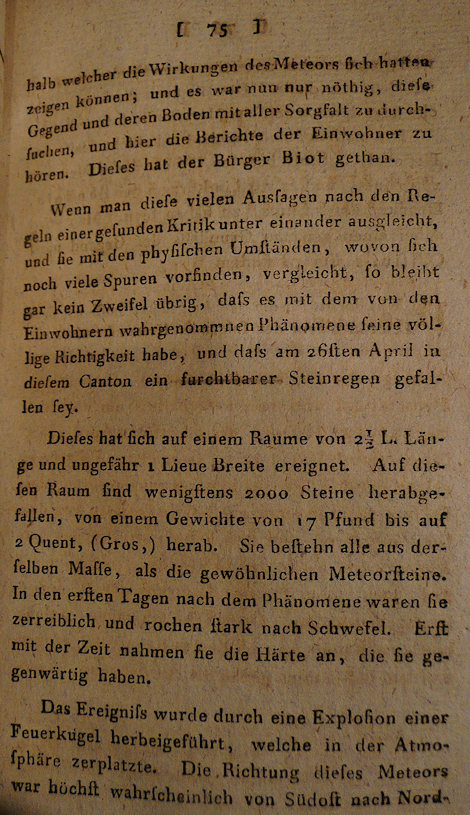

| A brief report from Biot prior to his visiting the L'Aigle fall site | |

| |

| |

| |